Right now, when donor governments give foreign aid, they do so on the basis of friendship and altruism. While that is certainly one reason, it’s not the whole story. Focusing only on that motivation leaves our partners filling in the gap with their own often destructive theories. In most cases, a powerful motivation for supporting development aid is the desire to live in a safer world. Helping other countries grow healthy and prosperous will makes us all safer. That is a perfectly acceptable reason to give aid.

If we speak honestly about the role of self-interest in international development, it would help us do our work better. It would empower host countries, reduce the idea that aid is basically a bribe to get something from the developing country, and improve community acceptance.

Empowering Host Countries

If we’re giving assistance for no reason other than the kindness of our hearts it puts us in a superior position. We’re the wealthy generous people, helping the poor who need our help. It is inherently disempowering to the people we work with – governments, communities, and individuals.

But, if we both have something to offer and something to gain – that is a partnership. Example: Haiti needs peace and prosperity. The US needs Haiti to stop exporting refugees and start buying the stuff we make. We can work together to make that happen. I think this explains, to a large degree, the success of social entrepreneurship. If you take generosity out of the equation, everyone is equal. And equality is a much better place to start.

Changing the Government View of Foreign Aid

Many, many, many foreign leaders see the world from a pure cold war realpolitik perspective. They assume that development aid is a quid pro quo and it’s given to win their geopolitical support. They genuinely don’t believe that aid could be given for another reason.

If development aid is just barter for geopolitical support, then it doesn’t matter if the aid projects are effective. It doesn’t matter what kind of work is supported. In fact, it doesn’t need to be development aid at all. It could just as easily be helicopters, weapons, or a new set of gold toilets for the dictator’s palace. Especially in countries where top-level leadership is corrupt, this doesn’t lead to host country support for development efforts.

While increased GDP and national prosperity benefits everyone, plenty of the short term efforts needed to bring that about have losers. Corrupt elites in particular tend to suffer, and they can and will oppose development projects for that reason. Strong support is needed from the host country is required to push past that. Knowing that the donor country values successful development efforts because it’s also dependent on the outcome helps to generate that support.

A caveat. Making donor interest in development clear could also lead to host government efforts to hold aid impact hostage. “If you care so much about regulatory reform, we’ll keep it from happening until you buy seven gold toilets.” But even that kind of gamesmanship is a game that takes impacts seriously, and is a form of empowerment, however unpleasant. And a donor can take the long view and refuse to play.

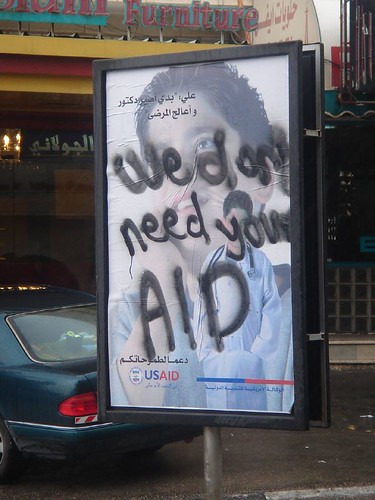

Community Acceptance

In my own career, I have been asked over and over by community leaders, local government officials, and plenty of other people why the US is funding the project I work for. They are curious, and they’re suspicious. They’ve seen enough American movies not to think Americans are saintly and loving. We must have a reason for doing something so good. But what is it? Having no clear answer makes us look suspicious.

Think of the famous case of the Nigerian religious leaders who refused polio vaccines. I strongly suspect that one reason they refused was that were looking for ulterior motives. Why would Americans want to send vaccines for Nigerian kids? Altruism alone didn’t make sense as an explanation, so they found another – the vaccines causes AIDS and sterility. They had also already been mistreated once by the international pharmaceutical industry, deepening their doubts. What if we’d said in the first place, “We want your kids to grow up strong and healthy so that they work hard, get rich, buy American products and don’t become terrorists.” That’s an ulterior motive that makes sense.

[…] all know this is the better approach – so why can’t we get there? If we’re giving assistance for no reason other than the kindness of our heart’s it puts us in a […]

Quoted you in my blog post, “The Dynamics of Giving and Receiving” at http://konpay.org/en/node/342

So I think I got kinda confused, between having low blood sugar from accidentally biking too far and not enough coffee, maybe, about how your two sections, “Empowering…” and “Changing the Government…” weren’t contradicting each other. Basically, I think because when I processed your “being honest about the quid pro quo of intl aid” through my belief that most people are going to attempt to milk every situation for all it’s worth (this clearly includes grad students, capitol hill interns, indian bureaucrats, aid workers at open-bar fundraisers and everyone i’ve ever worked for or with), I got back to your part about the cold war-style realpolitik think you’re talking about–the US wants friendly nations, who sell their natural resources cheaply and buy our processed goods at inflated prices and don’t kick up too much of a fuss, and the govts of the poor countries want golden crappers.

So I guess reading over what I just wrote it seems that I’m assuming that “US interests” are always selfishly in favor of US citizens and “poor country’s interests” are always in favor of corrupt leaders, which isn’t the case, obviously, just the stereotype of the relationship, and therefore easiest to use as a questionably-relevant “example”

ANYWAYS, the point of all that is that it really only seems like you’re advocating for some sort of semantic shift though you also seem to imply that this kind of “honesty” has been going on all along, minus a few select exceptions (which perhaps prove the rule?).

Not sure where I’m actually going with all of this, I’ve been kinda scattered all day, but it just made me think of a lot of different critiques of development that I’ve heard, notably those by Escobar (forget his first name, but he’s Colombian if I remember), whose basic thesis is that all development is a sham, and simply a new form of colonialism to bring the poorer states more fully under control of a northern-dominated global economy. To a lesser extent it makes me think of James Ferguson, but I think favorably this time, in that development has been said to de-politicize structural inequalities, and theoretically at least this a strategy to keep those as part of the mix. As long as you’re keeping the problems that the current power relations would create for this.

Oops, that went on too long, and I’m not sure if it’s coherent. Just my five-and-a-half cents.

I am advocating not just a semantic shift, but a new way of looking at development. It’s not just about the poor parts of the world, because everyone gains from global prosperity.

This is one of the best critiques of the current development landscape that I have seen in a long time. How do we make this happen?

[…] Alanna Shaikh argues that in this context, it doesn’t make sense to claim that we are giving aid out of the pure goodness of our heart. It not only puts us in a superior position which we may not deserve, but it’s likely to be disbelieved. So how about we tell the truth? “We want your kids to grow up strong and healthy so that they work hard, get rich, buy American products and don’t become terrorists.” That’s an ulterior motive that makes sense. […]

A refreshing look at how recipients feel about AID. I also see the first comment over and over again as so many have their hand out, if you’re a white guy wandering around in Ghana, as i was this winter.

However, I’ve met many altruistic people, mostly in small NGOs, looking for a way to get help to some small communities they’ve befriended . . . so many different faces to our human realities . . .