1. It focuses on AIDS, TB, or malaria but is not coordinating or harmonized with global fund activities in country.

2. The staff are all clinicians, with no public health people.

3. The staff are all public health people, with no clinicians.

4. There is no plan to involve local or national health authorities in the project.

5. The project director is a clinician with no management experience.

6. It is planning on developing its own training content instead of adapting existing curricula to the current situation.

7. It depends on practicing physicians to serve as trainers, but has no plan to teach them the skills they will need to become trainers.

8. There are no women on staff.

9. It ignores the role of nurses in health care.

10. The underlying conceptual model doesn’t make any sense or staff have trouble explaining it in a way that makes sense.

11. The only monitoring indicator is how many people were trained.

12. Training success is identified by pre and post tests of participant knowledge instead of testing their skills and whether they are actually using new skills in practice.

Special guest additions:

13. Local partners/beneficiaries cheerfully insist that another expat program manager is the ONLY WAY to make the next phase sustainable… (from Tales from the Hood)

14. It’s a two-year contract and the only local staff are secretaries and drivers. (from Texas in Africa)

15. You visit the public health office and they want to know why you’re taking away their public health volunteers. (from Good Intentions Are Not Enough)

16. The per diem for your capacity building event is less than that for the World Bank project just down the road. (from Ian Thorpe)

________________________

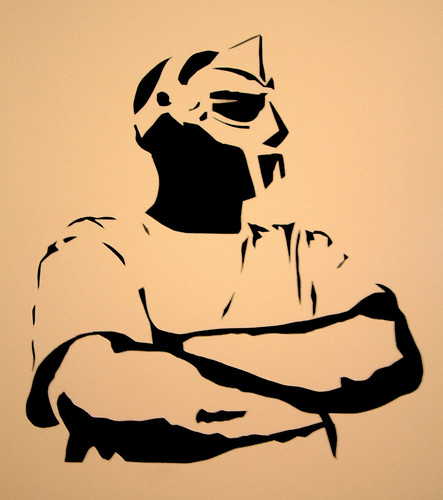

Photo Credit: REDRUM AYS

Chosen because searching for “doom” on flickr gets scary quickly, and my initials are AYS