I’m going to start with #9, because a lot of you asked about it. And I don’t want people thinking I was suggesting we convert people to, well, anything. No pith helmets, bibles, Korans, or books of Mormon here. Development has nothing – nothing – to do with salvation.

But missionaries do have a model we can learn from, at least the ones that I have met. They come into a country with a long-term commitment. They don’t just want immediate results; they want souls. Missionaries bring their families and children with them, and those children go to local schools. They live in houses that are nice by local standards, but not in the expat palaces your average foreigner inhabits. They bring their stuff with them in suitcases, not container ships.

Missionaries don’t try to do any soul-saving at first, spending a minimum of six months learning local language and culture. Mormons are renowned for their language skills. And once they have learned it, they stick around, spending years or even decades in country. They devote themselves to work in one particular place.

Compare that to your average expatriate working in development, for a donor or implementing a project. The expat lives in a little bubble of fake-home, cushioned by consumable shipments, huge shipping allowances, and hardship pay. With air conditioning and heating to ensure they’re even in a different climate. And they stay in one place for approximately 35 seconds.

Good people don’t have time to get great, and average people don’t even have time to get good. Complicated programs suffer as a result, and funding is biased toward things that are easy to implement and understand. No one has time to learn local context.

Donor governments rarely have people in place for longer than five years. In some cases, it’s not even allowed. Implementers are the same way. Three to five years, on average. The incentives are to keep moving from place to place. If you get a job in, say, Hanoi, while you’re already living in Hanoi, do you get housing and shipping and expat allowances? No. You get brought on as a local hire, and whatever salary they think you’ll settle for. If you want the big package, you apply for a job somewhere else.

And the ambitious, hard-working people who are good at running programs are usually chasing that big package. Think of the one guy you know who’s been in country for ten years, taking jobs with different projects as he can find them. Is he full of useful his skills and local knowledge? No, mostly he’s just a loser. Usually he doesn’t even have language skills to show for his decade of residence. If you set things up so that the ambitious people need to hop, then they will hop. The only ones who stay in place will be the people without the ability to move on. That doesn’t support good program management.

It’s even more painful with the donor types. At least program staff are bound by the specific terms of their grant or contract. An incompetent or philosophically opposed country director can only do so much damage. Every two or three years, someone brand new comes in, with the authority to radically alter all current programs. There’s a six month learning curve while they sort out their job and get some clue about the country. Then a nice two years, at best, of reasonably competent donor oversight, and then they’re emotionally checked out and focused on the next posting.

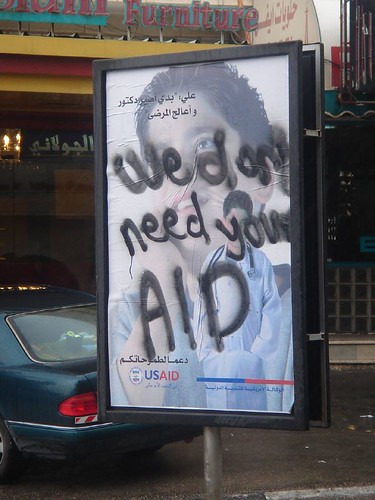

I’ve seen USAID country directors come in and kill programs that they thought weren’t working. And they were, but they were also hard to understand. Too hard to figure out in a couple weeks of reading reports.

Host country donor staff make a major difference in institutional competence, but it’s a rare donor who lets national staff run their programs. The fear is corruption, mostly, but there is also a capacity problem. The people with the education and skills to really run a donor program aren’t working for USAID, World Bank, or CIDA salaries.

Two years of reasonably competent donor oversight is a depressing best case scenario. When you have a really good donor representative, they are like an extra brain for your efforts. They can help you dodge problems, adapt quickly to challenges, and negotiate different government relationships. It’s a synergy that can make all the difference.

And it pretty much never happens. More often than not, your funder’s representative doesn’t speak the local language and doesn’t even know the nation’s major cities before they land. No matter how smart or committed you are, you don’t have time in a few years to get up to speed enough to be really useful. One of the very few things we know about what works in development is that your interventions need to be precisely targeted to the local context. We can’t do that if nobody knows enough about the local context to make that happen. And how do you take a long view on development when no one stays for enough time to think that way?

So that’s what we can learn from missionaries. Stick around until you know what you’re doing. Project managers, and donor representatives, should have regional knowledge and language skills. They should be deeply steeped in local culture. We need incentives to get good people to stay in one place and become experts at it. Well, first we need it to be permitted. Then we need incentives.

If we’re uncomfortable keeping country directors around for the long haul because of corruption concerns, then we could keep other people in country instead. Technical people, for example. You could have some just-rotated-in manager making the final decisions, guided by a team who’s been working in this context long enough to know what works. You also need host country nationals in as many positions of authority as possible. Get past those corruption fears with good financial controls, ethics training, and employee mentoring. (Yes, it’s an incomplete solution, but so is rotating people constantly to keep them from getting attached.)

———-

Photo credit: bp6316

Chosen because they look exactly like the missionary kids I see in Tajikistan.