My first couple of overseas jobs were pretty much just being the native English speaker on staff. Right after undergrad, I was an intern with the American University in Cairo. I drafted or edited every piece of writing that came out of our office. Later on, after my master’s degree, I was an intern again. And I drafted and edited, again. My international health degree was all well and good, but what they really needed was someone to make their grant applications sound good. My experience isn’t uncommon; I’d argue that it’s even the norm.

In other words, young Americans get jobs because the language of global health is English. Through nothing more than luck, we – literally – speak the language of power, and we can use that to get jobs.

I’ll repeat that, because it sucks so much. We get jobs because of an accident of birth.

Most of us go on to get jobs where we’re useful for other reasons. I’ve got a decent set of technical and managerial skills now; I am pretty sure I could get hired on those alone. But I don’t have to be hired on those alone. This makes me a direct beneficiary of global inequality, even in a field that is committed to eradicating inequality.

Because of the way the field is designed.

My Russian is seriously ungrammatical, my Uzbek is irrelevant in most countries, and my French is much better written than spoken. But hey, I speak English, so none of that matters.

On the other hand, I had a colleague once. A genuinely brilliant woman, with a PhD and an MD and fluent in three languages. Her English wasn’t great, though. So most people thought she was kind of silly.

Tech tools may help this. There aren’t a lot of global health problems with obvious (rather than complex) technical fixes, but the language problem is one of them. It seems to get better every day.

Google translate is breaking down a lot of barriers. There are people I email in English and paste the Russian google translate text underneath my original letter. They reply in Russian with the machine English below. I can read the auto-English and use it as a guide to the original Russian. That’s a huge step forward for everyone.

Lingvo is very popular among my Central Asian colleagues. It helps everybody make their way through unfamiliar English vocabulary, and it really seems to help people with writing. There are a few errors in Lingvo, especially with medical language, that I have seen so many times that I recognize them. But it’s a great start.

Software tricks are just the start, though. Helping people get better at using the language of power is a short-term fix. What we need is a system which doesn’t treat English speakers like they’re smarter than everyone else – a system where every language is a language of power.

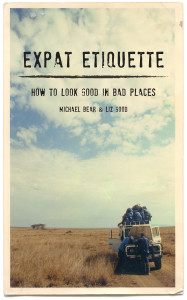

(photo credit: me)

Some of you may have noticed I started using all my own pictures in this blog a while ago. I pull them from my

Some of you may have noticed I started using all my own pictures in this blog a while ago. I pull them from my