Note: August is looking like a crazy and stressful month for me, with no time to blog here. To make sure no one gets bored and abandons me, I am going to re-run some of my favorite posts from the past.

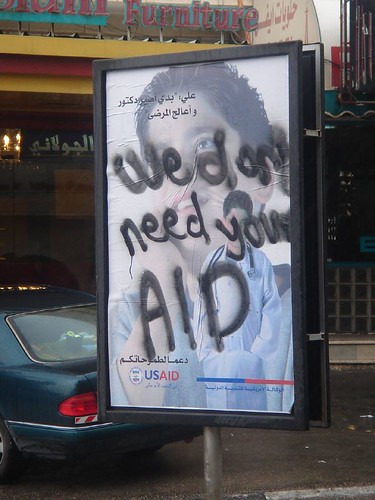

Give money. Don’t send food, bottled water, clothing or useful-seeming stuff. Give money.

Your old stuff costs money to ship. It is almost always cheaper to just buy it in country, and doing it that way benefits the local economy. It’s also more respectful to survivors of humanitarian emergencies, and allows relief agencies to procure exactly what is needed instead of struggling to find a use for randomly selected used junk. Disaster News Network talks about the used clothes problem in “The Trouble with Trousers.” which features a really depressing anecdote about Hurricane Hugo.

Your food costs money to ship, too. It is probably not food anyone in the recipient area would recognize. How exactly will the people of Burma know what to do with canned refried beans or artichoke hearts? Sending donated American food doesn’t drive income to local farmers or help local retailers start selling again. Buying in-country gets food people will actually understand how to cook and supports the local economy.

Here’s another example – some people wanted to send their old tents to China to house earthquake survivors. A sweet idea – provide quick, free housing. But every different kind of tent would have different set-up instructions, and how many people save their tent instructions once they’ve learned how to do it? It would take a huge time investment in figuring out each type of tent, and then training for the people in China who had to set up the tents. All of this time translates to a delay in providing housing, and it’s time used by paid staff, which means it is also squandered money.

Interaction, the coalition of disaster-relief NGOs, has a nice piece about why cash donations are most effective. They mention needs-based procurement, efficient delivery, lower costs, economic support, and cultural and environmental appropriateness as advantages of cash. World Volunteer Web has a good explanation too, breaking down the myths about post-disaster aid.

Usually people end these kinds of articles with links to the three or so places who will take your old clothes and possessions for international donation. I am not going to do it. Don’t waste everyone’s effort that way. Give your old stuff to Goodwill, the Salvation Army, or St. Vincent de Paul; they’ll make the best use of it. They’ll sell your things locally and use the money for their charitable purposes.

Giving stuff instead of money is easy for you, it’s cheaper for you, and it’s quick. It is not quick, easy, or affordable for the NGOs who are actually trying to help people.

If you want to help, give money.

[Picture of old clothes in Haiti from Flickr by Vanessa Bertozzi]