I have a confession to make: I am a fan. I read fan fiction. I participate in Livejournal communities. I have actually written fan fiction on occasion. It’s been a great hobby in a life where I can’t have hobbies that involve material things, and fan fiction has saved me more than once from death by boredom on trips too long to carry as many books as I need.

It’s traditional to pretend to be ashamed of this hobby, but I’m not. It’s been crucial to my understanding of social media, community, and the way the world has shifted to a new participatory culture. I am proud to be a textual poacher. This level playing field has even changed the way I see international development. And sometimes fans do wonderful things.

Which is a long way of getting to this post by Laurenist. In it, she deconstructs a new charity started by Misha Collins, the actor who plays Castiel on Supernatural. Here’s how she begins:

Now, Misha is attempting to once again tap his social networking prowess (and large fanbase) to raise funds for a new charity, Random Acts. Not awesome. (Sadface.)

Don’t get me wrong. I like charities! I like Misha! I want Misha’s charity to be one that I like. Unfortunately, it seems the people behind it have good intentions, but as we in the international development blogger community know, “Good intentions are not enough.”

Let’s look at how Random Acts says it’s going to spend the money it raises:

- 33% will be divided between the orphanages we support in Haiti

- 15% will go to support victims of the horrific flooding in Pakistan

- 51.99% will go to support random acts of kindness all around the world

- .01% will be spent bribing public officials

She has two major criticisms: 1) Orphanages are a bad idea and 2) Supporting random acts of kindness is not an effective use of money. I agree with her on both points. Orphanages are a bad idea, almost always. Saundra can tell you why. And the whole random acts idea strikes me as kind of weak. A lot of feel-good; not much actual result.

But.

Misha Collins actually responded to Laurenist’s post with a well-thought-out comment, and here’s what he had to say about the “random acts” portion of his charity: “Part of what made me want to do this project was seeing so many of my followers on Twitter putting so much energy and so many resources into fandom. I think all of that energy is great, but my thinking was, perhaps, if we could harness a fraction of those resources (both creative and fiscal), we could put some of this c-list idolatry to good use.”

He’s got a point. Fans are completely off the hook crazy. I know this because I am one. I once sent a postcard to David Hewlett that said “how are you so awesome?” I have seen every movie Josh Charles ever appeared in, and that takes some serious endurance. Small wonder Misha Collins wants to tap this fanatical surplus.

The thing is, fans are crazy because being a fan is fun. It’s not meaningful, Henry Jenkins aside. It’s not purposeful. It’s just fun. People don’t do fannish things because they want to be useful. They do it to entertain themselves. While a Misha Collins doing-serious-things charity probably wouldn’t capture fannish attention, maybe his doing-silly-things charity will. And while those silly kind things may not be terribly effective, they are not, as the comments on Laurenist’s post pointed out, worthless.

Misha Collins, in his own way, knows the community he’s dealing with: nutso fans. He’s designed a charity that will appeal to nutso fans and use their energy for good. So, this time, I have to say – more power to him. (Except for the orphanages.)

———–

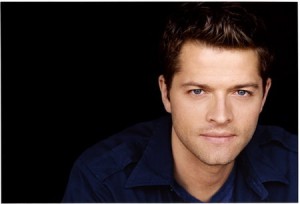

Yep, that’s Misha Collins.